Rafael Guastavino Structural Tile Arch System

20 Beautiful “Structural Art” Projects

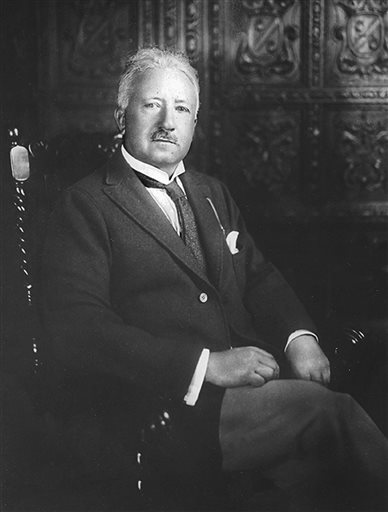

Rafael Guastavino was a Spanish architect, engineer, and “master builder” who is famous for the architectural terra cotta tile vault and arch system that he designed and constructed in the late 1800s.

Rafael was born in Valencia, Spain in 1842.

He trained as an architect and developed his own system of building which he called Cohesive Construction.

Cohesive Construction featured interlocking terr-cotta tiles held together with mortar to form timbrel vaults. This method required quick-drying cement called Portland Cement, which was hard to get outside of the USA.

So in 1881, Gustavino and his 8-year old son Rafael Jr. sailed on a ship bound for New York.

Though Rafael spoke no English, he had $40,000 and extensive knowledge of the construction technique that he introduced to the American architectural community.

The Guastavino Tile Arch System was patented in the United States in 1885, then Rafael saw his business take off.

In the following decades, his method would be utilized in hundreds of prestigious buildings across the United States.

Significance of Guastavino’s Tiled Arch System

Guastavino wrote extensively about his system of “Cohesive Construction”.

He believed that these vaults represented an innovation in structural engineering.

The tiled arch system provided solutions that were impossible with traditional masonry arches and vaults due to its lighter weight and fireproof properties.

Construction

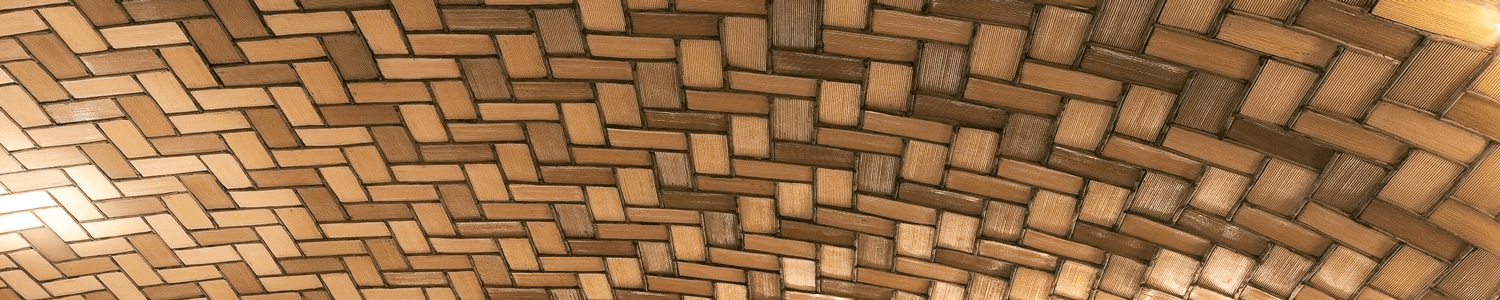

Guastavino’s terracotta tiles are standardized at less than an inch (25 mm) thick, and about 6 inches (150 mm) by 12 inches (300 mm) across.

They are usually set in three herringbone-pattern courses with a sandwich of thin layers of Portland cement.

Unlike heavier stone construction, these tile domes could be built without centering. Each tile relies on the quick-drying cement developed by the company, Portland Cement.

Akoustolith, a special sound-absorbing tile, was one of several trade names used by Guastavino.

All Guastavino projects built after 1908, were the work of his son, Rafael Jr.

______________________________

18 Beautiful Guastavino Projects

______________________________

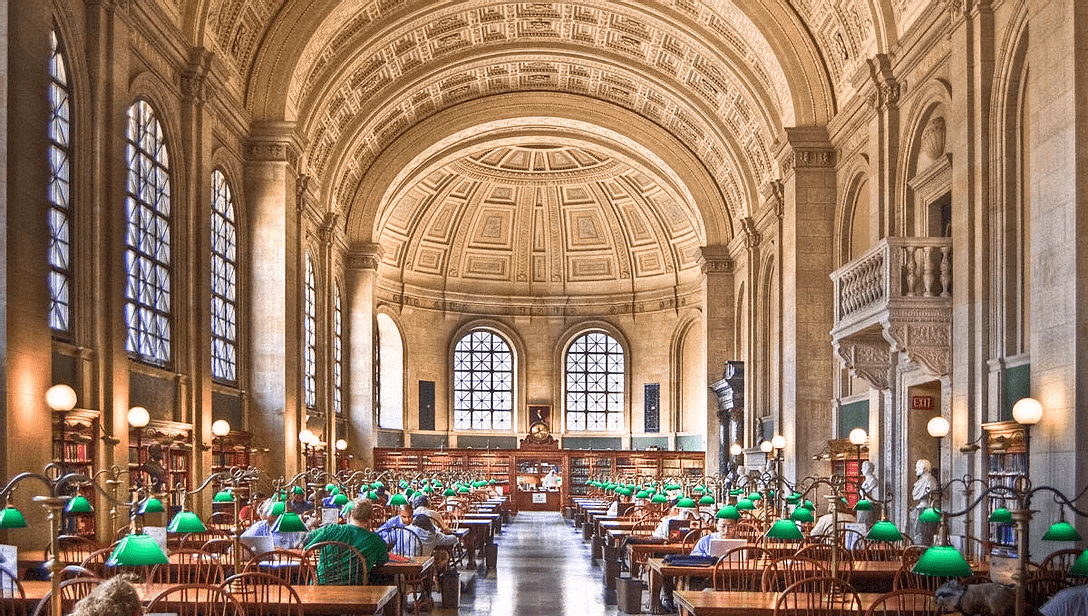

Boston Public Library

(1895)

From 1888 to 1895, Rafael laid tile in the Boston Public Library.

This was Guastavino’s first major American commission, the starting point for a company that would go on to construct vaults in over 600 buildings throughout the country.

His signature vaulted ceilings are featured prominently in the McKim Building’s lobby and map room.

_______________________________

City Hall Subway Station

New York (1904)

The abandoned City Hall subway station in New York City features the colorful vaulted Guastavino tile ceilings.

The station is visible only to passengers from subway cars as they pass through, and is accented with skylights and chandeliers.

When the New York City subway first opened, the City Hall station was referred to as “an underground cathedral,” according to John Ochsendorf, head of the Guastavino Research Project at MIT.

Ochsendorf said, “The public was afraid to go underground at that time and so these vaults and this beautiful decorative, colorful ceiling really helped people feel comfortable in a grand space below the city.”

With its stunning tile work and stained glass windows, the station was designed to be the crown jewel of the New York City subway system.

The station has been closed since 1945 due to its curved platform, which was deemed too short for longer trains that were later used.

.

.

_______________________________

Church of the Intercession

Trinity Church, Wall Street, NYC

This landmarked church was designed by architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (who is buried in the nave) as a chapel for Trinity Church Wall Street.

The complex includes three buildings and a cloister garth garden. The Guastavinos tiled the vaulting in cloister garth, the Crypt Chapel, and possibly in the Lady Chapel in the nave as well.

_______________________________

Grand Central Oyster Bar & Restaurant

New York (1913)

The magic of Grand Central Oyster Bar is in the layers of tile.

There are four layers in total, built from the ground up without the safety net of additional supports from below.

Altogether, the layers create a seal much like a brick oven, ensuring that the structure will stay intact even in the most devastating fire. It’s nearly indestructible.

Guastavino tiles cover the Oyster Bar inside Grand Central Station in NYC.

_______________________________

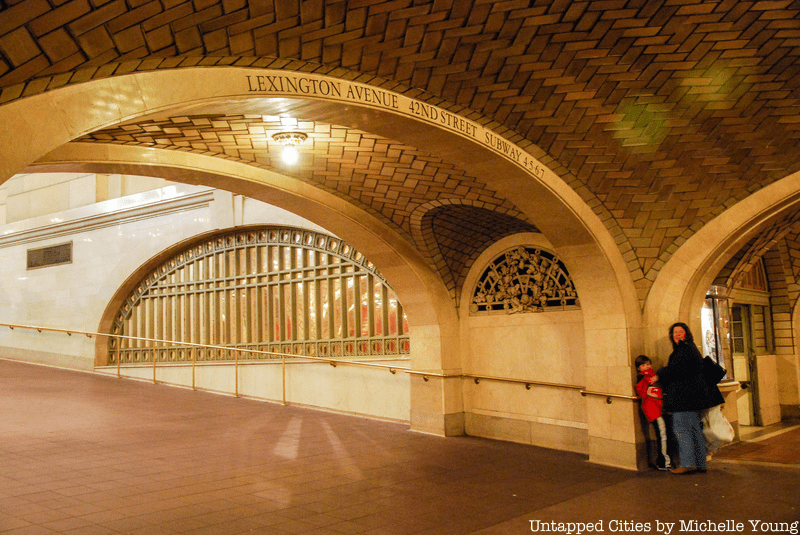

Whispering Gallery

Grand Central Terminal, NYC

The acoustic pockets of the Guastavino-tiled vaults in the Grand Central Terminal‘s Whispering Gallery act as the perfect acoustic pathway for messages.

When a visitor whispers in one of the gallery’s four corners, the sound will carry up through the timbrel vaulted ceiling and across diagonally to another corner.

The Registry Room at Ellis Island

NYC (1918)

The registry room at Ellis Island, where up to 5,000 immigrants a day were processed, is the largest and perhaps most important space on the island.

Guastavino’s tilework was added in 1918, 18 years after the room was opened.

Having experienced Ellis Island as an incoming immigrant, in 1917 the Rafael Guastavino was commissioned to rebuild the ceiling of the Ellis Island Great Hall.

The Guastavinos set 28,832 tiles into a self-supporting interlocking 56-foot high ceiling grid so durable and strong that during the restoration project of the 1980s, only 17 of those tiles needed replacing.

The Boathouse at Prospect Park

Brooklyn, New York

(1905)

The Boathouse in Prospect Park is a Beaux-Arts building with beautiful floor-to-ceiling windows and Tuscan columns, Guastavino tile ceilings, a hand-painted mural, a covered balcony, and a large terrace overlooking the scenic Lullwater Bridge.

It was one of the first buildings in New York City to be declared an historic landmark.

Vanderbilt Hotel

New York (1913)

The Della Robbia Room of the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York has Guastavino decorative tiled vaulting.

St. Paul’s Chapel

Columbia University, New York

St. Paul’s Chapel, located on the Columbia University campus between Buell Hall and Avery Hall has Guastavino tiles on both the timbrel vaulted staircase and the dome.

The staircase may have 2-3 layers of Guastavino tiles, whereas the dome may consist of as many as 5 or 6 layers of tiles.

The tile work was commissioned as part of the master plan for the campus.

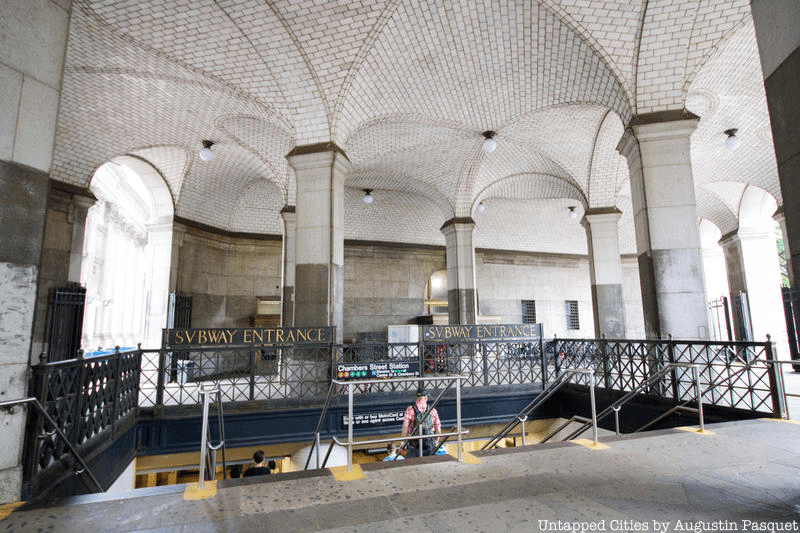

Municipal Building

Chambers Street, NYC

The Manhattan Municipal Building was the first to incorporate a subway station in its base, and it’s regarded as one of the most beautiful stations in the city, featuring 11 columns.

The south wing of the Municipal building on Chambers Street is fitted with a vaulted tile ceiling, though not in the characteristic herringbone pattern.

Bronx Zoo Elephant House

Bronx, NY

Architect: Heins & La Farge

The entrance to the Bronx Zoo elephant house — now the Zoo Center — has two adjacent domes overhead.

The domes are lined with the characteristic herringbone pattern of Guastavino tiles.

The Bronx Zoo Elephant House is the centerpiece of the zoo’s highly ornamented, Beaux-Arts pavilions designed by Heins & La Farge.

Today, the space is home to monitors, Komodo dragons, and southern white rhinoceros, but make sure to look up and spend time studying the grandeur of the Guastavinos’ work.

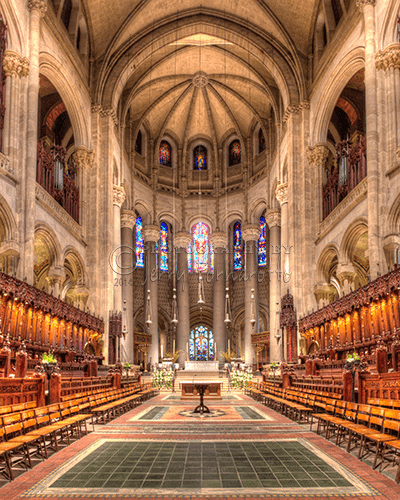

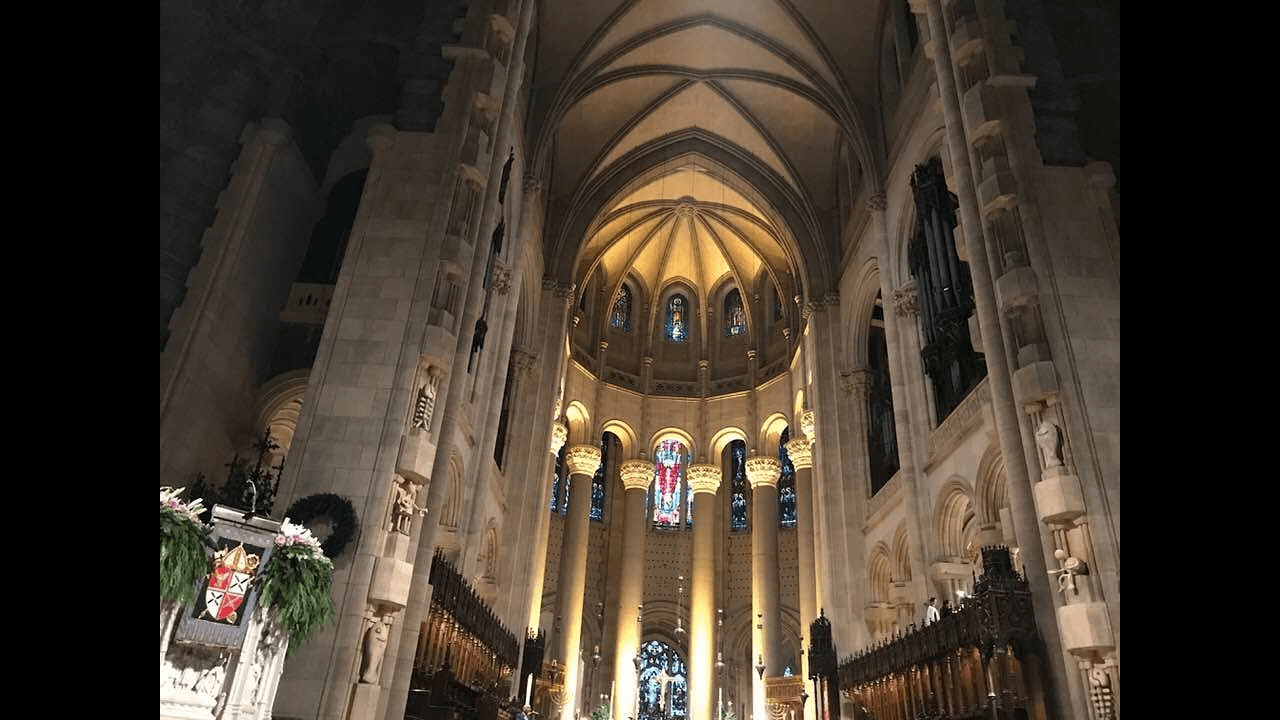

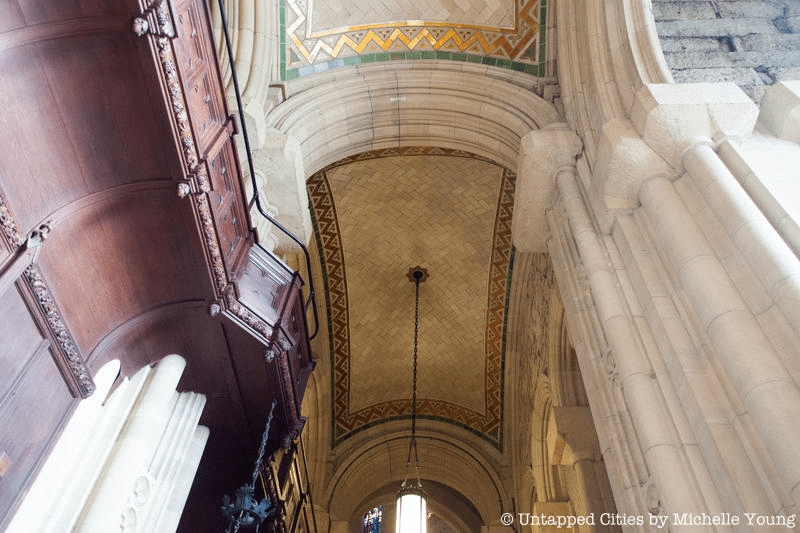

Cathedral of St John the Divine

New York City

After the success of the Elephant House, Guastavino again worked with Heins & La Farge at the Cathedral of St. John Divine.

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is the world’s largest cathedral but still remains unfinished.

In cross-shaped churches, a dome is constructed over the intersection of the four arms of the cross; a junction called the “crossing.”

Guastavino tiles were used to build the dome that hovers over St. John the Divine cathedral’s crossing, the side aisles of the nave, as well as the staircases.

The tiles are also in several of the chapels, the crypt, and the spiral staircases on either side of the altar.

The Guastavino tile system lends major stability to the dome, also making it one of the largest free-standing domes in the world.

It is now near impossible that the cathedral will ever be completed, as new apartment buildings have risen where the transepts would have been built.

![]()

![]()

![]()

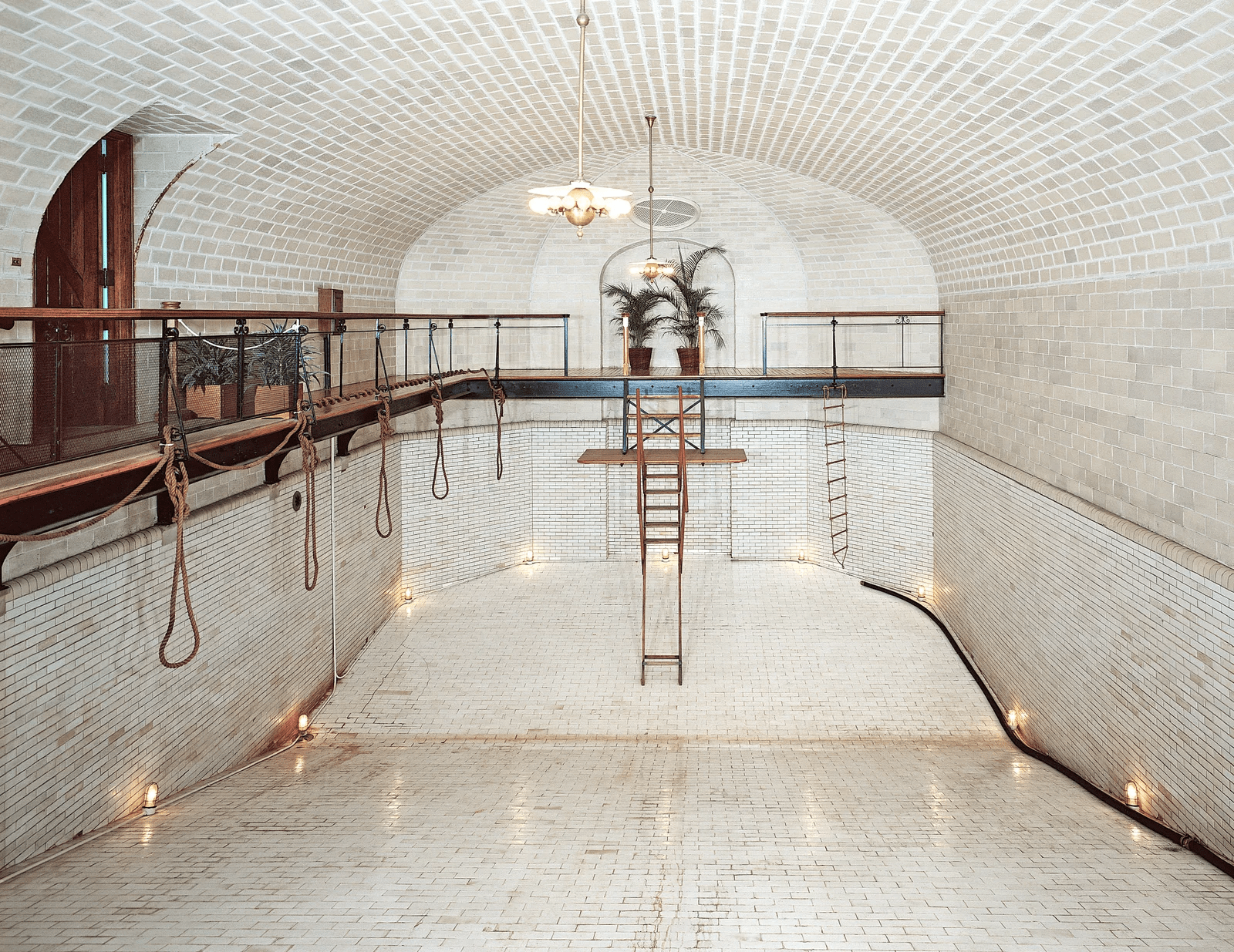

The Biltmore Estate

Asheville, North Carolina

(1895)

The Biltmore Estate is America’s largest home.

Guastavino’s tilework can be seen in the swimming pool, the Porte-cochere, and the winter garden.

Guastavino eventually retired to Asheville before he died in 1908.

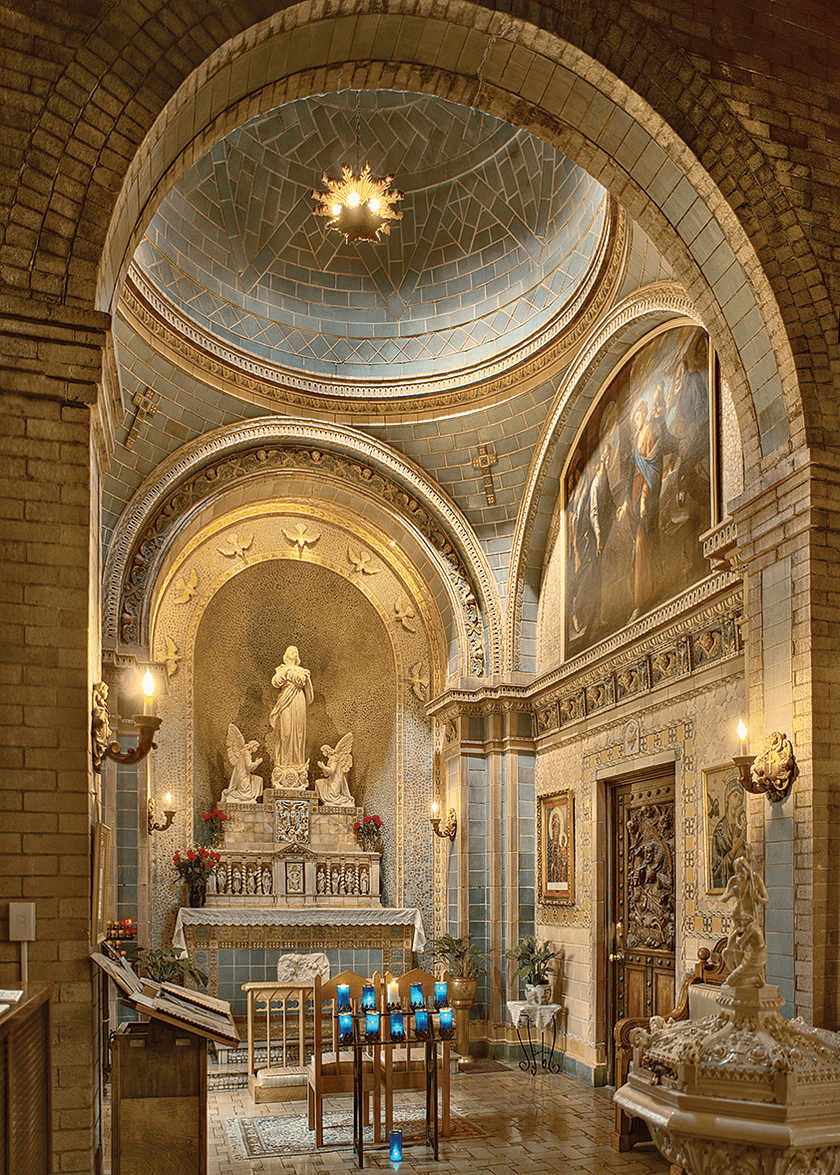

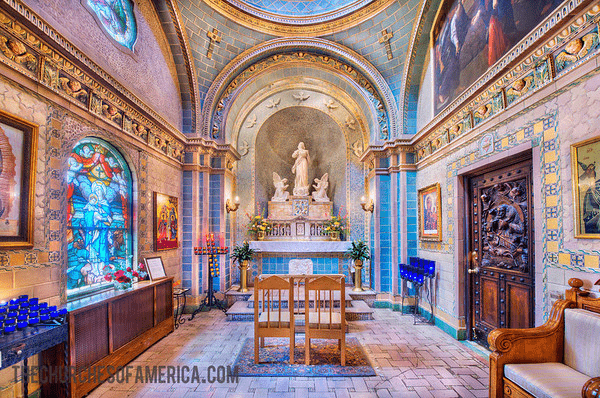

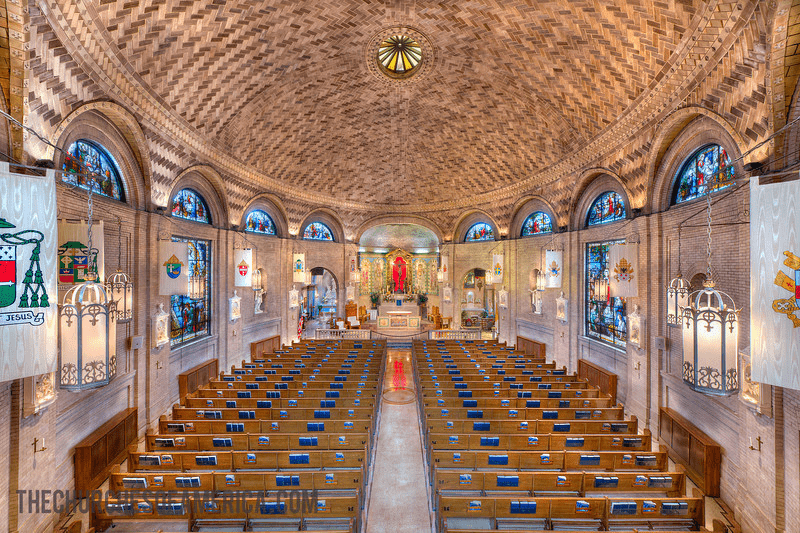

The Basilica of Saint Lawrence

Asheville, North Carolina

This is the only building in the United States that the elder Guastavino designed from the ground up.

The Spanish baroque design of the basilica reflects Guastavino’s own heritage.

Rafael Guastavino came to North Carolina to work on the Biltmore House in the early 1890s. Liking the area, he began to buy land south of Black Mountain.

As a Catholic, he became involved in efforts to build a new Catholic church in the nearby Asheville area and was a major benefactor.

Rafael Guastavino died in 1908 at his home in North Carolina, with the great church still unfinished.

A high requiem mass was held for him in the nearly completed building.

The building eventually housed the crypt of Rafael Guastavino.

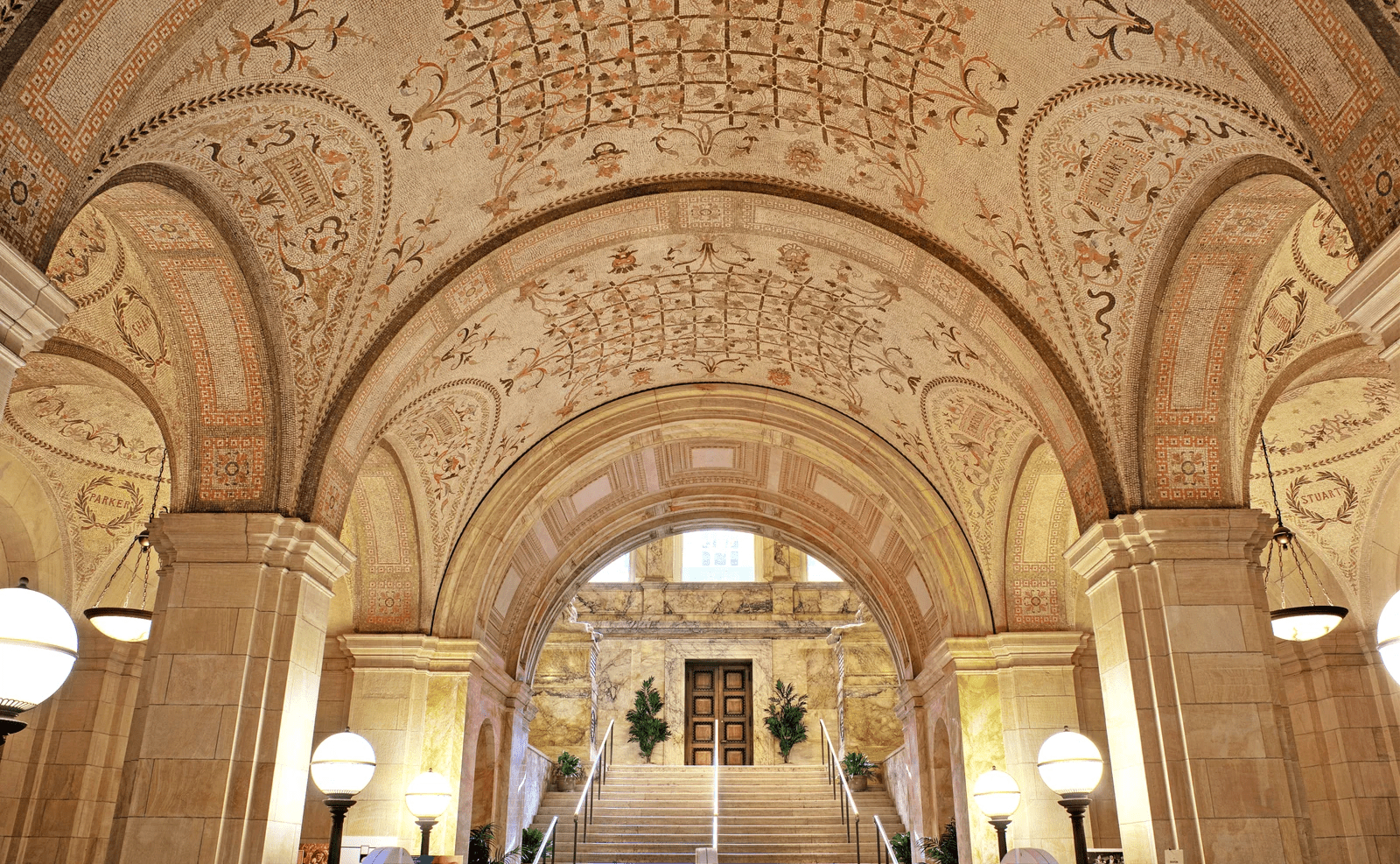

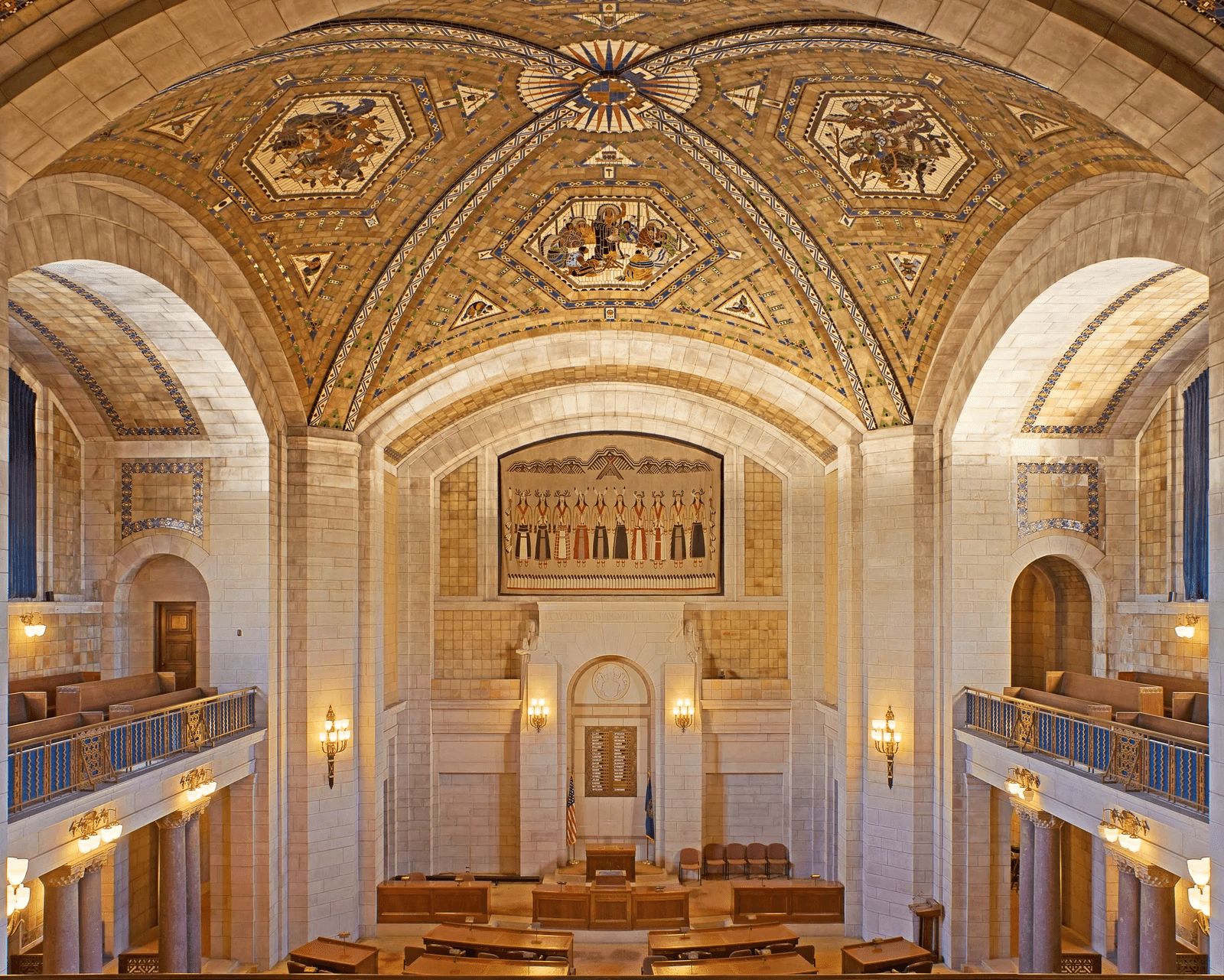

The Nebraska State Capitol Building

(1932)

The Nebraska State Capitol took over 10 years to complete.

It was one of the Guastavinos’ largest projects. They manufactured more tile for the Capitol than for any of their other works.

Hildreth Meière created the decorative tile designs, which were then laid by Rafael Guastavino Jr.

Built 1925 – The theme of the Vestibule is “Gifts of Nature to Man on the Plains”.

The sun, an important gift of nature, is represented in the center of Hildrethe Meiere’s Guastavino tile dome, and is surrounded by a circular mosaic representing agricultural products of Nebraska.

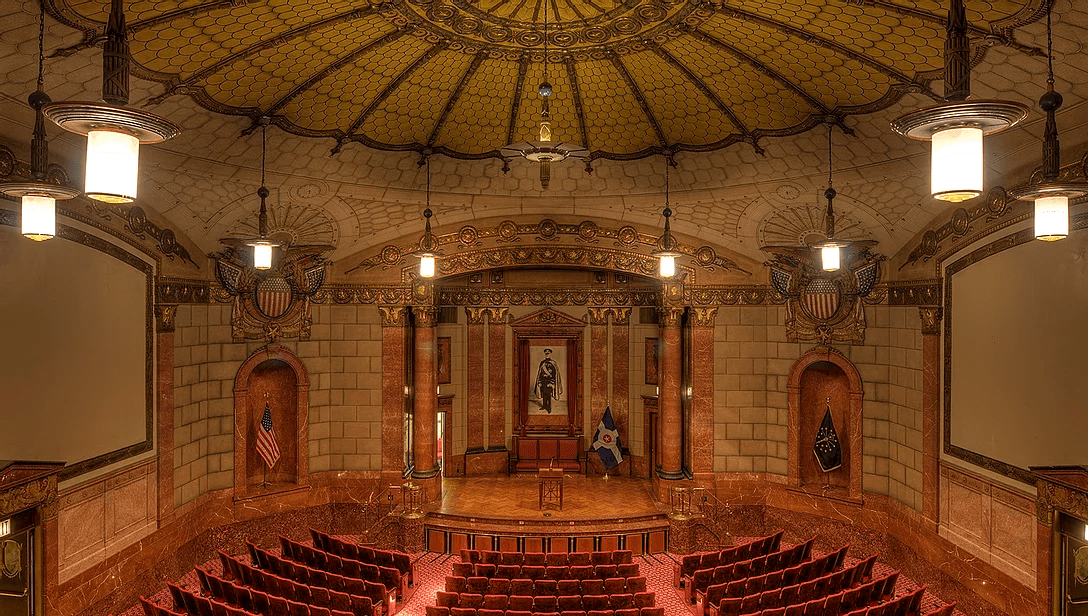

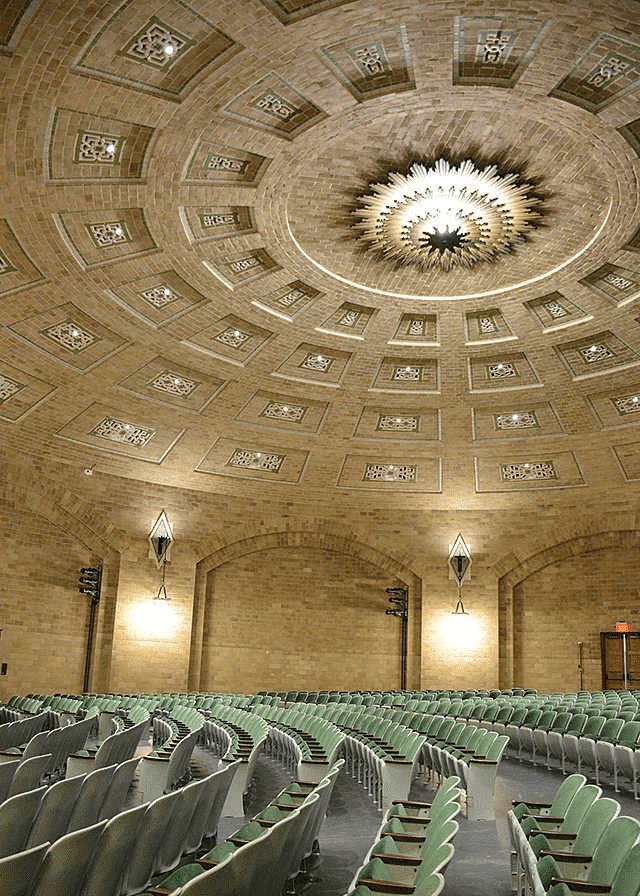

Indiana War Memorial

Indiana

The War Memorial includes the 500-seat Pershing Auditorium, which is acoustically perfect and features Guastavino acoustical tile in a domed ceiling.

The Harrison Auditorium

University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Museum

It was renovated in 2019.

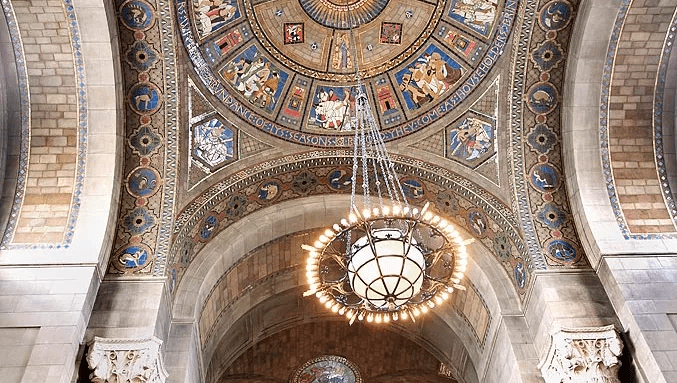

Washington National Cathedral

District of Columbia (1916)

The vaulting in the north transept ceiling was finished with Akoustilith tile, a cast stone tile patented in 1916 by the Guastavino family.

The tile had significant absorptive qualities that improved the ability for readers and preachers to be heard in worship spaces.

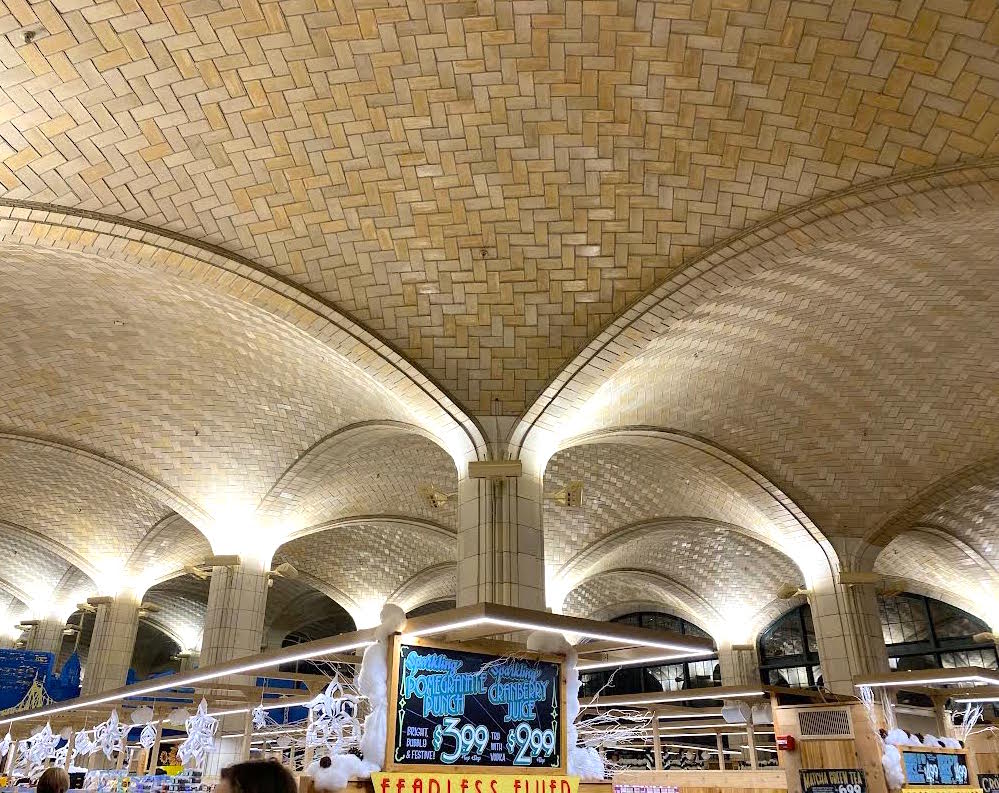

Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge

New York (1909)

The Queensboro Bridge opened in 1909, with the Manhattan approach supported on Guastavino tile vaults.

Guastavino and his son, Rafael Jr. tiled the vaulted space under the Queensboro Bridge.

The space was originally a food market called the Bridgemarket that closed during the Great Depression, and it has reopened several times as different businesses.

Today it is a Trader Joes.

The Tile House

BayShore, NY

The Tile House, as the locals call it, is a home built in N.Y. by Rafael Guastavino Jr.

Guastavino built this house when he was working on Grand Central.

Archival sources

The Guastavino Company was headquartered in Woburn, Massachusetts, in a building of their own design which still stands today.

The records and drawings of the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company are preserved by the Department of Drawings & Archives in the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University in New York City.

Rafael Guastavino Structural Tile

Their work is also in the Ford Buildings of Berry College, Rome, GA. How Martha Berry convinced them to do this is a marvel.